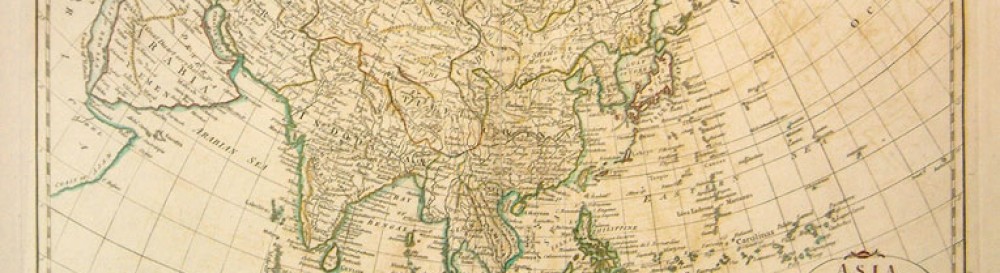

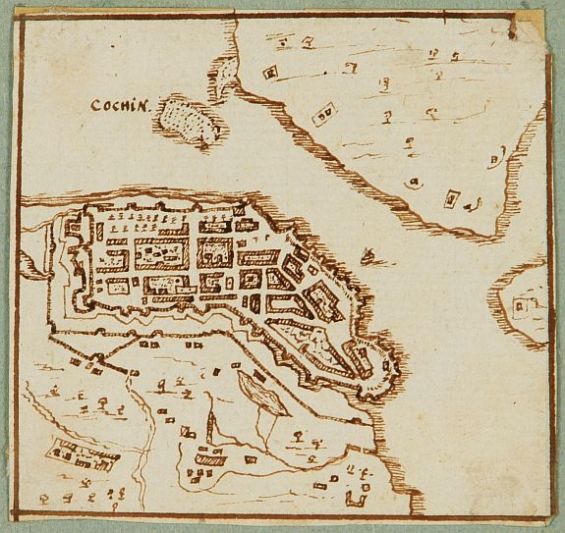

You’ve come back to Cochin many times. It is a layered place, a many threaded tangle of Portuguese, Dutch, British, Chinese, Arabic and Indian. The quiet streets are filled with European style houses and Keralan buildings. There are churches, synagogues, mosques, Hindu temples. Enormous Chinese fishing nets, a royal palace built by the Dutch and filled with Hindu mural work. An early global city. You don’t know why you keep coming back, but you do. Because you love it. There’s nothing rational about that.

Arriving this time you notice immediately that Cochin has changed. You have never been here in February, in the high tourist season. You don’t remember there ever being quite so many boutique hotels or art galleries or cafés. Each year they seem to push further from the waterfront, and more of the old town is pimped out with boutique hotels, fine dinning, and cafes, not to mention that there’s something called The Biennale, which is, apparently, an exhibit of art by several dozen international and Indian artists that has been put up throughout the town with all the subtly of an occupying army. Some of the art is street art. Layers of paper on four-hundred year old walls, harmlessly pasted, drawn over with faces and multi-colored birds. You almost like it, but don’t and don’t know why.

There are more tourists than you have ever seen in India. A different kind of tourist. Older, European, rich. India has always attracted profit seekers and self-explorers, the materially and the spiritually rapacious. But these people are maybe the first in history to come to India only for a holiday.

You consider them darkly: their sun hats and fanny-packs, camera in one hand, coconut with a straw in the other hand. Though you’re sure they mean well, you imagine the things that they are going to say about India’s vibrant colors, it’s incongruous poverty and beauty, how cheap the shopping is and how regrettably dirty it can sometimes be outside of one’s hotels. These are tourists who, you suspect, land in Cochin for three days before flying to Agra to see the Taj, who tour Delhi in AC cars, and fly home having snapped some photos of India gate and Qutub Minar. Who neither know nor care to know what’s between those places. The big expanses and the millions of lives that their jet passes over. In your less charitable moments you fantasize about picking their pockets or conning them into pricey sightseeing tours of Naxilite country. Though of course, what all of this really means is that you are feeling a sharp ambivalence because, no matter what your visa says, you’re still a tourist too.

*

In the evening you walk down the promenade by the sea and watch the sun set. From this vantage point the sunsets are beautiful, though the sun is invariably swallowed by a bank of clouds some degrees above the horizon. Slightly to the right of that point there is an enormous structure jutting out into the water, a natural gas plant. At night it comes alive with a billion star-like electric lights and it is somehow the most beautiful thing you can imagine, an enormous celestial beast hunched over the sea. The smaller lights of cruise ships and warships and freighters and fishing boats dance by underneath.

This is an excellent place to sit and consider your life, and you have done so multiple times on four different stays in Cochin over the past 3 years. Once wondering if you were in love with a certain person, and once pondering how really miserable it was going to be to go back to Jaipur. Once speculating what life in Delhi would be like. And now you are examining, out loud to the friend who has accompanied you here, the various intricacies of getting into/not getting into graduate school and the way the rest of your life will unfold and how complicated it all is. And though you have never found answers to any of those questions, you are at least perceptibly more calm when you are in Cochin.

*

The next day you walk to Mattancherry, which is an area south of Cochin known for its historic buildings including a very old synagogue and a beautiful palace that the Dutch built for one of the local rulers and that Indian artists filled with the most astounding murals. You’ve been to both of these several times.

But this time what strikes you the most is not the murals, or the old historically-Jewish section of town, which is now filled with antique stores and art galleries and which you don’t even bother going to this time round. What strikes you is the in between, the section of the city between Fort Kochi and Mattancherry.

From the jetty down to the Dutch Palace you follow a narrow road between shops and warehouses. For a brief stretch—a couple of kilometers—after the street-side restaurants and the guest houses and before the organic spice boutiques and antique shops you enter something else, another kind of space. The road is sometimes clogged with trucks, parked to unload while auto-rickshaws and pedestrians try to work their way around what little street is left. The gutters are open and filled with murky water and trash, the occasional rat. Goats wander. Most of the shops sell wholesale and the shopkeepers are content to ignore you, knowing that you will not buy fifty-pound bags of rice or flour. Gateways lead to warehouses and court yards filled with tea and spices, the smell stifling, even in the street.

Some of the shops sell hardware, gears and tackle-block, mechanisms of metal and grease, rust and dull paint. One shop’s walls are partitioned into one hundred and forty-seven compartments, each holding a different type or size of hardware: screws and bolts, washers and rods. These stores sell the rough things that a place needs to run, paper and chemicals and paint, the pieces of machines, the raw goods that are turned into food. The shops and restaurants are deep and well shaded from the sun, places where tea is drunk, places of simple food, where cigarettes and beedies are lit from a lighter hanging on a string on the wall or a perpetually burning piece of cord.

What you like the most is that the place ignores you. It lets you through without trying to sell to you, without trying to get you to buy. It’s image and atmosphere is uncrafted, it evolved this way because it works this way and the beauty in it could not be recreated or planned or perfected.

*

On the day that you leave you wander back towards the waterfront one more time and walk past the group of women who sell cheap jewelry and beads under the shade of the big trees in the park. It occurs to you that they are wearing Rajasthani fashions and you realize that though you’ve seen them before you’ve never wondered what they’re doing in Kerala, as far from Rajasthan as you can get.

You walk to a café, but something about those women will not leave you alone, so you double back and then hesitate and then talk to one of the women in Hindi. She tells you that they’re indeed from Rajasthan, moving around for work, staying in Cochin for last six years or maybe it’s the last six months, you lose her meaning somewhere in the language.

This brief encounter shakes you. There’s so much that you want to ask these women, but somehow it feels wrong to do so. Somehow you are afraid that you will stumble over your very bad Hindi. It is easier to walk away. You want to ask them how they learned about this place, what it was that pushed them here or drew them. You want to ask them what it is like, to be dry-lands people by the sea. You want to tell them that you’ve seen their place, their state, a village like the one they may be from. You’ve even lived in Rajasthan, though that means little enough. You want to ask them if they believe that this place is real, the round white tourists with money falling our of their pockets, the art, the boutique hotels that used to be fishermen’s homes. If they have as much trouble understanding it as you do.

But you can’t ask. Maybe because your tongue will tie up and maybe because it seems unfair, knowing that after this encounter you will go and drink an espresso and they will go on selling their wares and at night they will go home. In the end you know that your presence is far more of a curiosity than theirs is.

“These are tourists… Who neither know nor care to know what’s between those places. The big expanses and the millions of lives that their jet passes over.”

Can totally relate with the depth, speculation and the kind of subjectivity in this post!