Far up over the riverbank, he wakes among the rocks and his mind is bothered by some lingering thing, a dream he almost had. The landscape sweeps out underneath—the boulder pile mountains, the banana groves, the river. The skeletons of temples hiding in the form of the earth. But the lingering thought is from before, from something he has seen in this day, before he slept. And some time later he realizes what it is, the statues of the women that he has seen in the ruined temples. The matching stone-carved women that stand in pairs at the temple gates. Some kind of guardians.

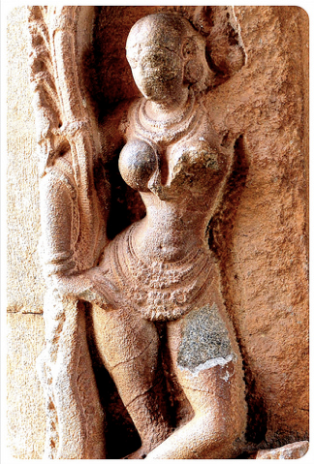

It is not until later that he hears her name. After he has gone back and searched the statues out and examined them. Ganga, the river goddess, bare breasted and standing astride a crocodile. One hand on her hip, one hand resting on the trunk of a tree. The hip and the waist a curve of liquid, dance, song, sex, water. Her form so fluid that it makes perfect sense when he learns that she is a river. The artist has captured life in the bending of the body, in the curves.

The statues stand in the temple gates at several sites. He counts them and then forgets. Somewhere around twenty, maybe eighteen or twenty-two. None of the statues are complete. Every single one is in some way imperfect, broken or worn away over the five hundred years since they were made. He can see the sculptor’s mistakes, the places where they miscalculated and created weaknesses in the stone, which cracked over time. Breasts, arms, and legs are most likely to be broken. Very few of the sculptures have more than one missing piece, though faces are generally gone. One breast may be broken. One hand. One leg. A shattered forearm can still imply grace.

At first he walks between them and sees only their form, the elegant sway. He begins to recreate the sculpture in his head, reassembling the pieces mentally. The faces are the most poorly preserved, very rarely smashed, but very often worn completely blank. He finds one eye, intact, and elsewhere an eyebrow. Most of the faces are worn away, but here and there he catches a mouth, a nose, begins to piece together a whole expression. He finds the details of necklaces and skirts, a bracelet on an ankle. Once, the exact shape of a hand, thumb and forefinger circled together, gripping a dangling earring.

But as he begins to study them he sees that these statues are not replicas of each other. Each version of Ganga is subtly unique, holds on to some aspect of itself even as time tries to take it away. Breasts are slightly uneven in size and tilt. Some wear a plain belt at their hips, while others’ skirts are adorned with a single perfect flower, others with five. He finds several distinct hair styles and multiple forms of jewelry. These discoveries of difference send him back and forth between the statues. He has to look and look again. He begins to realize that, among the most completed faces he can detect wildly different expressions, from somber to joyful. He learns that there is no single Ganga. It is not a simple reconstruction.